Before there was a Detroit Institute of Arts, there was the Detroit Museum of Art. And before there was the Detroit Museum of Art, there was a Detroit Art Loan Exhibition [1]. It was in 1883 that the first major art exhibition was held in Detroit. The exhibition contained over forty-eight hundred items, including oil paintings, watercolors, sculptures, bronzes, prints and drawings by American and European artists displayed in twenty-six large rooms [2]. For ten weeks, from September 1 through November 14, “134,925 people paid twenty-five cents to visit the exhibit hall” [3]. The exhibition’s success proved that “the city of Detroit has taste and wealth enough to found and maintain an art gallery” [2,4].

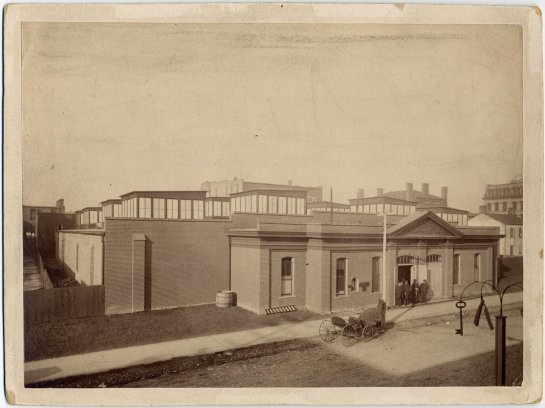

Temporary brick building built to house the Art Loan Exhibition for 10 weeks in 1883. The building was subsequently converted into a roller-skating rink [4,5].

During the exhibition, a newsletter, The Detroit Art Loan Record, was published. The complete set can be found in The Detroit art loan record. One volume. September 1 to November 14, 1883 [6]. The newsletter hosted the (rather one-sided) discussion concerning the Nude in Art that appears interesting.

The work of art that provoked public discussion was Nymphs at the Bath by William-Adolphe Bouguereau [7,8]. The painting now known as The Nymphaeum (1878) [9] was created as an “exhibition piece” and displayed at the 1878 Universal Exposition in Paris. At present, the painting is in the Haggin Museum in Stockton, California (Location: Haggin Room) [10]. The Nymphs at the Bath were the part of the Hazeltine Collection and came to Detroit from Chicago [11]. A superb collection of thirty-one paintings “secured from the Art Department of the Chicago Exhibition” represented “more than $100,000 in priced value” [6] (p. 148). ($100,000 in 1883 equals to $2,331,817 in 2018 [12]). The Bouguereau was “held at $25,000”. Despite the fact that Bouguereau was considered as the great master, the acceptance of the “Nymphs” for exhibition was not easy (in contrast to another Bouguereau – “The Twins,” valued at $20,000). Three ladies from a women’s Organizing Committee were invited to Chicago in a hope to convince them that the picture “would not offend”.

The ladies gazed in disapproving silence until suddenly, looking at Bouguereau’s “The Nymphs at the Bath,” Mrs. Stewart exclaimed, “Why they are dolls. Life sized figures would be objectionable but when they are so small the effect is quite different.” Almost in relief the ladies agreed [11] (p. 160).

The size of the painting is 57 x 82 1/2 inches (145 x 210 cm).

The information about the reception of the painting at the exhibition is contradictory and unclear. Cheboygan Democrat from 8 November 1883 informed its readers that “Bouguereau’s painting of “The Nymphs at the Bath” was hung in an obscure corner and was quite neglected by visitors, who had heard it was improper” [13]. In The Detroit Art Loan Record, one can read that Room K, where the painting was exhibited, suddenly became “more of a resort for gentlemen than for ladies” and that “a room 30 feet square is constantly filled with admiring male gazers” [6] (p. 189).

The Record offered “the masterly, if not conclusive, argument of President Bascom”, who believed that the practice of nudity in art “violates the laws of propriety”.

The source of this practice is against it. It is Grecian, pagan, in its origin. Because the Art of Greece has kindled our own, it does not thereby follow that a Christian people are to adopt entire the Art of an idolatrous and licentious people. <…> The Grecians were accustomed to the naked athlete, and had a right, which our artists and critics have not, to know the nude human form. Our artists reach their knowledge second-hand or surreptitiously then flaunt it against decency. <…> The forerunner of nude Art with us ought to be nude life. <…> Facts are against this practice. The nudity of Grecian and Italian Art in part sprang from and in part occasioned the licentiousness of those communities. [6] (p. 185-186).

In her newsletter column, Mrs. Sara M. Skinner wrote the letters from “Bessie” to “Mollie”:

I can’t help thinking that if the influence of nudity in Art is good, its influence in reality would be good also. Now here is a problem for you to analyze: If 13 females on a canvas are so beautiful with no clothes on, that a room 30 feet square is constantly filled with admiring male gazers, why should 1 poor live female be so condemned when she appears on the street partly covered with clothes? If nudity is ennobling, “purifying” to the beholder, why do education and civilization put clothes onto people? I tell you, Mollie, as you know, that women, whether nymph-like or not, never bathe nudely in the presence of each other, and lovely woman is so much of a prude that she for one needs not the nude to “purify” her. (The last words of Bessie [6], p. 189)

Looking at The Nymphaeum by Bouguereau, one can indeed find 13 “stark-naked nymphs” with “impossibly smooth skins” and “harmoniously proportioned bodies” bathing “in a secret woodland grotto, with a satyr and Greek youth peeping through the bushes”, just a “pure fantasy, meant to transport the viewer from the day-to-day cares and boredom of modern urban life into a serene daydream of classical Arcadia” [10].

I think maybe Bessie was right,

if the influence of nudity in Art is good, its influence in reality would be good also.

References

[1] Ardelia Lee, Before There Was A Detroit Institute Of Arts, There Was The Detroit Museum Of Art, Daily Detroit, Aug 21, 2016

http://www.dailydetroit.com/2016/08/21/detroit-institute-arts-detroit-museum-art/

[2] Bill Loomis, On This Day in Detroit History, Arcadia Publishing, 2016

https://books.google.com/books?id=AMA4CwAAQBAJ

[3] Arthur M. Woodford, This is Detroit, 1701-2001, Wayne State University Press, 2001

https://books.google.com/books?id=cVP055AfqNEC

[4] Jeffrey Abt, A Museum on the Verge: A Socioeconomic History of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1882-2000, Wayne State University Press, 2001

https://books.google.com/books?id=DSAj_yQRt9wC

[5] Art Loan Exhibition Hall | Detroit Public Library

https://digitalcollections.detroitpubliclibrary.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A148360

[6] The Detroit art loan record. One volume. September 1 to November 14, 1883, Detroit, H.A. & K.B.Ford, 1883

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000247585

[7] William-Adolphe Bouguereau – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William-Adolphe_Bouguereau

[8] Bouguereau, William Adolphe 1825-1905 [WorldCat Identities]

https://www.worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n85059001/

[9] William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) – The Nymphaeum (1878). From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William-Adolphe_Bouguereau_(1825-1905)_-_The_Nymphaeum_(1878).jpg

[10] The Nymphaeum c. 1878 by Bouguereau, William-Adolphe – The Haggin Museum

http://hagginmuseum.org/Collections/WilliamAdolpheBouguereau/TheNymphaeum

[11] Alice Tarbell Crathern, In Detroit courage was the fashion; the contribution of women to the development of Detroit from 1701 to 1951, Detroit, Wayne University Press, 1953

https://archive.org/details/indetroitcourage00cratrich

[12] 1883 dollars in 2018 | Inflation Calculator

http://www.in2013dollars.com/1883-dollars-in-2018

[13] Cheboygan Democrat, 8 November 1883

https://digmichnews.cmich.edu/cgi-bin/michigan?a=d&d=CheboyganCD18831108-01.1.2